For 35 years, the Center for International Private Enterprise has participated in a worldwide effort to build the institutions of markets and democracy. During that time, CIPE has developed a number of innovative programs in partnership with business associations, think tanks, and other nongovernmental organizations throughout emerging markets and developing countries. CIPE is a pioneer in the field of development and is unique in its ability to bring the business perspective to democracy assistance.

The Formation of CIPE

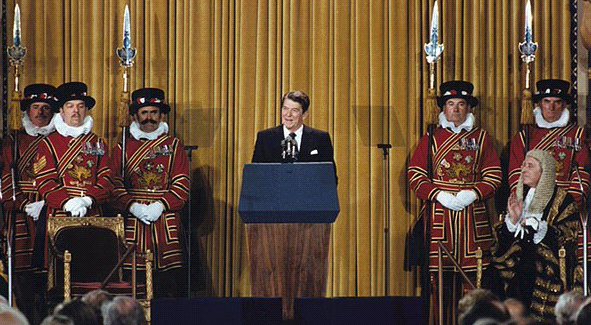

CIPE was launched as an outcome of the Democracy Program, which President Ronald Reagan called for in 1982. In a speech at the Palace of Westminster, Reagan made a case for the creation of a mechanism to encourage democratic development around the world. The Democracy Program included representatives from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (including myself), the AFL-CIO, and the Republican and Democratic national committees, as well as various members of Congress and leading foreign policy experts. The idea was to bring together the United States’ pluralist constituencies under a nongovernmental umbrella to help strengthen democracy abroad. The result was the formation of the National Endowment for Democracy in 1983 along with the creation of CIPE, the International Republican Institute, the National Democratic Institute, and the American Center for International Labor Solidarity .[1]

In his Westminster address to members of the British Parliament, Reagan presented a challenge to everyone involved in this work:

“The objective I propose is quite simple to state: to foster the infrastructure of democracy — the system of a free press, unions, political parties, universities — which allows a people to choose their own way, their own culture, to reconcile their own differences through peaceful means. … It is time that we committed ourselves as a nation, in both the public and private sectors, to assisting democratic development.”[2]

At that time, there was a debate within the Democracy Program about whether there is, in fact, a relationship between democracy and free enterprise. To my mind, the relationship was obvious since I had written on preconditions for democracy as a doctoral student and had also worked for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for five years. One of the program representatives who doubted this relationship pointed to the existence of free-market dictatorships, such as Chile under Augusto Pinochet. However, Chile’s political left and right later agreed to continue using market reforms as the framework for the economy when they signed a National Accord that re-established democracy. The same skeptic also cited Yugoslavia as an example of a perceived democratic socialist economy. The breakup of Yugoslavia, however, demonstrated the fallacy of democratic socialism.

One of the most telling moments in this debate occurred when Lane Kirkland, then head of the AFL-CIO, declared during a Democracy Program meeting, “Of course we need free enterprise. Without free enterprise, you can’t have free unions. We need the U.S. Chamber.” This was a pivotal moment for the creation of CIPE, which was founded as a non-profit affiliate of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Within just over a year, the Democracy Program had presented its recommendations to Congress, resulting in legislation authorizing funding for the NED as a private organization with a mandate to support democratic development around the world. CIPE was created soon after.

Nations’ Routes to Democracy

Each nation must chart its own course to building the infrastructure of democracy; there is no one-size-fits-all solution. In 1983, when Reagan signed the NED’s authorizing legislation into law, he noted:

“Now we’re not naive. We’re not trying to create imitations of the American system around the world. There’s no simple cookbook recipe for political development that is right for all people, and there’s no timetable. While democratic principles and basic institutions are universal, democratic development must take into account historic, cultural, and social conditions.

“Each nation, each movement will find its own route. And, in the process, we’ll learn much of value for ourselves. Patience and respect for different political and cultural traditions will be the hallmark of our effort. But the combination of our ideas is healthy. And it’s in this spirit that the National Endowment reaches out to people everywhere —and will reach out to those who can make a difference now and to those who will guide the destiny of their people in the future.”[3]

In other words, societies cannot export democracy. Nor can they import policy frameworks, institutions, or other principal elements of development. While countries have to adopt rule of law, property rights, sound governance, and a host of other features of a modern developed economy, the path to reform and to acquiring these institutions will differ according to each country’s unique characteristics.

It is therefore vital to begin reform with a fundamental analysis of each country’s conditions in order to understand why things work the way they do. This was the insight of CIPE’s first major partner: Hernando de Soto, founder of the Institute for Liberty and Democracy in Peru. He asked why “people who have adopted every other Western invention, from the paper clip to the nuclear reactor, have not been able to produce sufficient capital to make their domestic capitalism work.”[4] He discovered that large numbers of Peruvian entrepreneurs operated outside the formal economy — without property rights or business licenses. These entrepreneurs were locked out of the formal economy because of overregulation, corruption, cronyism, and red tape. Inspired by De Soto’s insights and research, the World Bank launched its influential “Doing Business” reports, which measure the barriers to registering and operating a business in nearly 200 economies worldwide.

In Egypt, CIPE came upon a prime example of the importance of cultural context to institutional reform. When CIPE co-hosted a conference to introduce corporate governance principles, the business and political leaders in attendance identified a unique challenge: the lack of a precise Arabic equivalent to the word “governance.” This linguistic barrier was a problem that went beyond semantics because it hampered implementation of the concept. Subsequently CIPE, the Egyptian Capital Market Association, and the Ministry of Foreign Trade supported a committee of Arabic linguistics experts to develop an appropriate term for governance. After more than a year of deliberation and consultation, the Arabic Linguistics Council approved hawkamat ash-sharikat — “the governance of companies” — as the Arabic term for corporate governance. Today, the term is used widely throughout the region and serves as a starting point for building a culture of good corporate governance.

Democracy and Development

Democracy promotes growth by encouraging economic reforms, increasing investments in human capital, and improving public goods.[5] Three central aspects of democratic governance have proved to be crucial to long-term economic and social development:

- A stable democratic system is the best guarantor of political stability, which is essential to long-term economic growth and private sector investment.

- Democratic practices such as transparency and accountability are necessary for effective and responsive government and efficient economic activity.

- Sound legal and regulatory codes backed by the rule of law must exist for businesses to thrive in a market economy.

Early on, CIPE adopted the insights of Nobel laureates Ronald Coase, Douglass North, and Oliver Williamson, who established the New Institutional Economics. This approach holds that the institutions of property rights, contracts, and rule of law are building blocks of market-oriented democracies and necessary to advance political and economic development. It is institutions that “define the incentive structure of societies and specifically economies.”[6]

The institutional approach says that rules shape human interaction and economic performance.[7] Put differently, the lasting success or failure of any transition to a democratic, market-oriented system depends on the design and functioning of the institutional framework. According to North, the entire history of economic growth can be summed up in one concept: moving from systems of personal exchange, in which individuals do business with people they know and trust, to systems of impersonal transactions, in which people do business at a distance with strangers. Market institutions make wider, impersonal exchange possible by controlling transaction costs, protecting property, and safeguarding individual rights.

However, the market framework cannot exist in a vacuum. Rather, it is the result of the political process, which establishes the rules of the economic game through laws and regulations. North points to “adaptive efficiency,” the degree to which institutions can adjust to change, as a hallmark of the democratic process. It is democracy’s adaptive efficiency that enables the long-term transition from barter to markets.

Debunking Development Myths

The role of the private sector in development is shrouded in certain misunderstandings, which are important to address. The first myth is that having a private sector is synonymous with having a market economy. When I was in Afghanistan talking to members of the Afghan Parliament, with President Hamid Karzai’s brother translating for me, I mentioned this myth. For example, under President Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, there were plenty of private enterprises, but it was not a market economy. Rather, it was a crony capitalist system. In fact, Filipinos were the ones who coined the phrase “crony capitalism.” Another example I mentioned was Indonesia under President Suharto. Unless you did business with the president’s family, you could not do business. At that point, three members of the Afghan Parliament raised their hands and exclaimed, “We think that’s what’s happening here!” The point is that in a market economy, the rules must be the same for all participants.

The second myth is that the business community is a monolith. Business communities in most countries are actually extremely diverse and include small and medium-sized enterprises, the informal sector, leading-edge firms, crony firms or “oligarchs,” and state-owned companies. Early on, CIPE learned that it was not possible to build a coalition between the informal sector and large corporations because their interests were divergent. The large-business sector viewed the informal sector as an opponent and a threat, while small and informal entrepreneurs saw the large-business sector as privileged capitalists. Every country also has a leading-edge sector of companies that want access to international capital and the ability to license technology. These companies have an interest in an open economy. By contrast, state-connected companies fear the loss of their privileged position and have an interest in a closed system. Therefore, although the majority of businesses in any given country want reforms, it is important to analyze the structure of the business system and the interests of different sectors.

The third myth is that if government gets out of the way, a market economy will emerge. This myth was dispelled after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Experts flooded into Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union and said, essentially, “Let’s take the government out of the economy, distribute state-owned property into private hands, and let the market take care of itself.” As it turned out, crony capitalists or oligarchs took control of the bulk of economic assets and took de-facto control of the political system. Government does have a significant role to play in underwriting fair, consistent rules and laws so that a strong market economy may emerge.

One story from Poland’s transition illustrates the challenges in creating market institutions. In 1989, the communist Polish United Workers’ Party proposed the Law on Economic Activity . The law included language to the effect that, notwithstanding any other feature of Polish law, anything that is not illegal is legal. Why would one need to say this? The communist system had been based on the idea that if something was not explicitly legal, it was illegal. Without a regulation granting the permission or right to do something, one could not do it. That meant that to build a market economy in these countries, an entire mindset would have to change from the ground up.

Building a Market Economy

Depending on a country’s governance and policy framework, entrepreneurs and competitive firms either flourish or languish. The distinctions among these frameworks were captured in the book “Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity” by William Baumol, Robert Litan, and Carl Schramm.[8] They note that although state-backed firms have become increasingly powerful in recent years, they do not offer good prospects for innovation and sustainable growth. The approach they recommend, which CIPE follows , is to cultivate entrepreneurial economies. This is done by empowering businesses to innovate and transition from micro-enterprises to small and medium-sized companies, boosting job creation and the economy in the process. Providing the institutional environment that fosters this transition is of key importance for poverty reduction and development.

Governments are often regarded as the leading force in building a strong investment climate, but this responsibility does not rest with them alone. Although the political will to implement reforms is key, no government can legislate the creation of an entrepreneurial economy from the top down. Such an economy needs active and engaged businesses to work with the government and provide guidance on reform priorities and policy solutions. The private sector shares the onus to lead on reforms.

In 2011, representatives of 160 countries and hundreds more organizations came together in Busan, Korea, to agree on a set of development principles, which became known as the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation.[9] I became involved in this partnership at the invitation of Brian Atwood, who served as USAID administrator and later the head of the OECD ’s Development Assistance Committee. At the Busan forum, representatives of the public and private sectors released a joint statement, which stressed inclusive dialogue as one of five shared principles for development cooperation. Inclusive dialogue serves to create a policy environment conducive to sustainable development.

Those of us from the private sector on the high-level panel insisted that the policy environment and policy dialogue were essential to accomplishing sustainable development. However, it is difficult to keep governments focused on the need for reform and dialogue. Governments often seek to bring in foreign direct investment through corporate public-private partnerships, but these are one-off deals. To attract FDI on a larger scale, societies should first create a sustainable development climate with a functioning market economy that encourages inclusive economic growth.

Moreover, when a few powerful business elites and cronies monopolize access to the government, the majority of legitimate business interests are rarely represented in a country’s political process. A broader business community must become engaged in the reform process to ensure that their voices are heard in the policy debate and that fair economic competition prevails. In turn, fair economic competition strengthens business diversity and pluralism, which creates a strong context for healthy political competition and checks on government power.

The CIPE Business Model

The foundation of CIPE’s “business model” is the idea of local ownership of reform initiatives, something that CIPE’s first leader, Mike Samuels, and I understood from the start. This idea crystallized at a meeting we had in 1983 with the Association of American Chambers of Commerce in Latin America, whose members included both U.S. and local companies in the region. The business representatives made a point that stuck with us: “You had better understand that we’re not sitting here in Latin America waiting for the United States to lecture us on how democracy works and the importance of free enterprise. You’re going to have to find local champions.”

Ever since, local partnerships have been integral to the CIPE business model. Local champions possess detailed knowledge of the business climate and the challenges and opportunities for reform. After all, local entrepreneurs know better than anyone which laws and regulations make it hard to do business in their countries, and how laws and regulations can be improved. CIPE looks to local champions for program ideas and recommendations and strives to give them a voice through capacity building, advocacy training, and technical support.

It was CIPE’s first partner, Hernando de Soto, who introduced CIPE to the economist Douglass North. De Soto worked with three of North’s graduate students to apply the lessons of institutional economics. The students performed the pioneering research on transaction costs in setting up a small garment firm. This was a tremendous example of a local partner bringing new ideas and local knowledge to a CIPE program. In turn, CIPE helped De Soto’s institute to design an economic reform agenda and an advocacy campaign based on increased citizen participation in decision-making.

Advocacy to remove barriers to business requires a framework for policy reforms. The “national business agenda” process provides such a framework that typifies CIPE’s model. President Jimmy Carter’s White House Conference on Small Business pioneered the business agenda process in 1980. For the first time, the White House conference brought together various constituencies, including small, medium, and large businesses from all over the country to identify common interests—not just what was good for small business, but also what was good for America. The conference led to the passage of a law that simplified paperwork to reduce the burden on small business. After the Carter administration, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce adopted the methodology of the small-business conference and continued it as the national business agenda.

A national business agenda aims to encourage investment and stimulate business activity, and it creates a platform for public-private dialogue. CIPE adapted this methodology internationally as an advocacy tool. Our maxim was, “You can’t export solutions, but you can share technology and techniques.” The process of creating an agenda gives form to CIPE’s core value of mobilizing local actors for effective local solutions. Through a focus group process, CIPE helps the local business community identify its priorities and builds a coalition to advocate for its agenda.

Taken all together, six elements mentioned above capture the CIPE business model: (1) Strengthen democracy and support market-oriented reform; (2) Empower private sector organizations; (3) Promote institutional reform; (4) Focus on advocacy; (5) Reinforce local ownership and accountability; and (6) Apply lessons learned. The model spells out CIPE’s approach to reform and the way CIPE pursues its mission. Because the elements are common across CIPE’s varied programs, they thread together CIPE’s four areas of focus.

CIPE’s Areas of Focus

CIPE implements programs across four focus areas: enterprise ecosystems, democratic governance, business advocacy, and anti-corruption and ethics. These programs build the foundations of democratic, market-oriented systems and create opportunities for citizens from many walks of life.

Enterprise Ecosystems

Building the institutions of a market economy means reducing barriers to doing business and promoting an inclusive entrepreneurial culture that provides opportunities for all citizens. By prioritizing the development of enterprise ecosystems, CIPE works to establish a level playing field and a healthy business environment for all entrepreneurs.

There are two different approaches to describing entrepreneurship ecosystems . In a narrow sense, some people refer to ecosystems as the network of business schools, finance institutions, incubators, and others that help entrepreneurs get started. CIPE’s definition of the entrepreneurship ecosystem is broader and encompasses the institutions of a market economy that enable free enterprise, such as the rule of law and property rights, as well as support networks for entrepreneurs.

The importance of the business environment became obvious to me early in my career while I was interviewing residents of Los Angeles’ blighted Watts and South-Central neighborhoods who had received assistance from the Minority Business Enterprise program. While conducting these interviews for a study, I frequently encountered wonderful business ideas but was surprised to find entrepreneurs implementing them in the San Fernando Valley rather than in their own neighborhoods. When I asked why, the response was, “Are you crazy? There’s no money here.” Our study determined that money coming into the neighborhoods did not produce a local multiplier effect. People would get paid and then spend their earnings elsewhere. As a result, there was no incentive to start a business there, and entrepreneurs were much better off opening a business in the Valley or in West LA. That is when it occurred to me that it is necessary to look at the overall economic environment. We cannot talk about entrepreneurship development without a focus on the entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Once governments remove barriers to entrepreneurship and private enterprise, companies can thrive. One observable result is a decline in informality. After Carter simplified and harmonized regulations, and Reagan deregulated the economy, the United States’ informal sector shrank considerably. The same result occurred in Peru after the government adopted De Soto’s recommended reforms to standardize business registration, simplify administrative processes, and issue property titles. It may not be every company that thrives in a market system. It may be new companies coming into the market, but these will create jobs, which may include workers who were once informal operators. This is a high-quality growth model, one in which growth is widespread and inclusive.

Democratic Governance

Of the major democracy assistance organizations, CIPE is one of the few that have consistently emphasized democratic governance. Politics is not just about electing leaders, but also about what happens between elections — in other words, the making of public decisions. Democratic governance, in which citizens have a say in a government’s decision making, is fundamental to ensuring that democracy delivers for all of society. An open, participatory governance process responds to the needs of citizens and businesses, resulting in better and fairer government policies.

CIPE’s experience in Hungary in the 1990s demonstrated how citizens’ input can inform sound decision-making. Formerly, the Hungarian government prohibited the release of draft legislation until it had passed the Parliament, and the legislative framework provided no opportunities for public notice or public comment. Recognizing this deficit of democratic governance, CIPE created a process for public input into the governing process. Jean Rogers, our country director at the time, held seminars on different legislative concepts. To garner a wide range of views, she invited an executive branch official who was drafting legislation, as well as business associations, NGOs, think tanks, and others to deliberate. Hungary ultimately changed its framework and adopted a public notice and comment period, legislative hearings, and so on.

Strong democratic governance is characterized by transparency and accountability in both the public and private sectors. CIPE became involved in corporate governance in response to the privatization of state-owned enterprises in Eastern Europe in the early 1990s. I was traveling around Eastern Europe with Professor Roman Frydman of New York University. On hearing about the privatizations, I asked, “How are they going to run these companies if nobody has ever governed a private company?” Nor did they have the legal and institutional structures of the market economy needed to drive internal corporate governance. CIPE went back to Frydman and commissioned its first corporate governance project, a project on governance education at Central European University.

Later, the OECD invited us to participate in the 2004 revision of its corporate governance principles, which covered the relationships between management, boards, shareholders, and other stakeholders. CIPE brought a focus on the external environment. In an OECD country, one can assume that the rule of law and private property rights exist. In non-OECD countries, one cannot expect the rule of law and private property rights to spontaneously take shape. We invited partners from emerging markets to the OECD review. The resulting revision incorporated the first principle on “ensuring the basis for an effective corporate governance framework,” which should “promote transparent and efficient markets” and “be consistent with the rule of law.”

Business Advocacy

CIPE empowers the private sector to actively participate in the democratic process through partnerships with local business associations, chambers of commerce, and think tanks. As an important segment of civil society, voluntary business associations act as the voice of business, bringing the issues companies face and possible solutions before policymakers. Their importance has long been noted, going back to Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” which described the roles of associations in preserving political independence and pursuing common aims. Through public policy advocacy, associations mobilize business perspectives, analyze options, and communicate them to decision-makers.

In order to perform their representative functions, associations around the world need to build their membership and strengthen their organizational management. One of the first priorities of CIPE’s business advocacy strategy was to create a training program for business association development. We looked at the Institute for Organization Management established by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation and decided that it was a good vehicle to adapt to other countries. In one of our first programs, we created the Latin American Institute of Organizational Management at the INCAE Business School in Costa Rica, where the program continues to this day. Strengthening business associations is about giving voice to diverse constituencies. In 2005, CIPE identified an opportunity for reform in Pakistan, where women could not serve on chamber of commerce boards or establish their own trade bodies. CIPE led an effort to reform an outdated regulation that governed the formation of chambers of commerce in Pakistan. In 2006, the revised Trade Organisations Ordinance created new self-governance mechanisms and, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, allowed for the creation of women’s chambers of commerce. Eight women’s chambers of commerce subsequently registered throughout the country. In 2017, CIPE joined with the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry to create the first-ever Women National Business Agenda for Pakistan, expressing women business owners’ recommended policies on small and medium enterprise, trade, and finance.

Anti-Corruption and Ethics

Businesses in developing countries are realizing that corruption costs them tremendous amounts of money and that they must do something to curb it. Corruption not only hurts the business community and citizens of developing countries economically, but also has a destabilizing effect on democracy and the well-being of a nation. Combating corruption can clear a path to broader governance reforms.

Companies should consider adopting voluntary standards such as Transparency International’s Business Principles for Countering Bribery,[10] the United Nations Global Compact, or sector-specific principles such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. In doing so, they can show their commitment to ethical and sustainable business while ensuring that effective internal policies strengthening anti-corruption and disclosure are in place. Corporate governance is at the heart of an anti-corruption program because you have to create incentives, mechanisms, and structures for companies to conduct business transparently.

Reducing or eliminating corruption creates business opportunities in international value chains, which in turn helps shape a country’s governance culture. The U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the OECD’s Anti-Bribery Principles are two provisions that affect how U.S. and multinational companies conduct business overseas. It is in the interest of these companies to work in emerging markets with local business associations and chambers of commerce whose anti-corruption goals they share. CIPE has worked in Thailand with the Institute of Directors to create an anti-corruption certification program, which has certified more than 200 companies. By engaging in collective action against corruption, domestic and foreign firms can help create a better business environment for all.

Conclusion

High-quality growth driven by the local private sector can significantly reduce poverty by creating jobs and income streams for the poor. Sustainability means that fundamental reforms and institutional changes drive growth. That growth must be inclusive. In many countries, between one-third and two-thirds of businesses are locked out of participation in formal economic growth because of their extralegal status and barriers to conducting business. To achieve inclusiveness, societies must open avenues through which the poor can acquire formal status. This in turn requires greater inclusiveness in policymaking.

Democratic channels of feedback and accountability aid the flow of information from private sector constituencies to policymakers, thus promoting the development of true market systems. Through accountability and open dialogue, democracies—not authoritarian regimes—are most likely to arrive at sustainable policies appropriate to local needs. Democracy does not always provide the quickest route to the most efficient economic policies. Yet, participatory governance has advantages over even elite technocrats when it comes to dealing with an evolving, uncertain world. Functioning democracies are flexible and adaptable. They may not always get policies right, but through accountability, learning, and the open exchange of information, they are more likely to arrive at sustainable policies—appropriate to the local context— in the long run.

In sum, top-down reforms built around experts, governments, and ministries must give way to bottom-up efforts that solve the key problem of the entrepreneur and build an enabling environment for private sector-led growth. Private sector organizations play a vital role in this process by bolstering company standards, public policy advocacy, and community engagement. CIPE’s purpose is not to promote private enterprise as such, but rather to support the institutional infrastructure of democracies that deliver for everyone.

Special thank you to Kathryn Walson and Kim E. Bettcher for their copy-editing work.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

[1] For more on the history and development of the National Endowment for Democracy, see David Lowe, “Idea to Reality: NED at 30,” posted on the endowment’s home page at www.ned.org/about/history/.

[2] President Ronald Reagan, “Promoting Democracy and Peace,” 1982, posted at http://www.ned.org/promoting-democracy-and-peace/

[3] “President Ronald Reagan’s Remarks at a White House Ceremony Inaugurating the National Endowment for Democracy,” 1983, posted at https://www.ned.org/president-ronald-reagans-remarks-at-a-white-house-ceremony-inaugurating-the-national-endowment-for-democracy/

[4] Hernando de Soto, “The Mystery of Capital,” Basic Books, 2000.

[5] Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson, “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” NBER, March 2014. See also Boris Begović, “How Democracy Influences Growth,” CIPE Economic Reform Feature Service (July 1, 2013).

[6] Douglass C. North, “Economic Performance Through Time,” Nobel Prize Lecture, December 9, 1993.

[7] Douglass C. North, “Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance,” Cambridge University Press, 1990.

[8] William J. Baumol, Robert E. Litan, and Carl J. Schramm, “Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism,” Yale, 2007; Robert E. Litan, “Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism: What Is a Market Economy and How Can It Deliver?” CIPE Economic Reform Feature Service (January 30, 2010).

[9] The Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, http://www.oecd.org/development/effectiveness/busanpartnership.htm

[10] Transparency International, Business Principles, 2013 edition is available at https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/business_principles_for_countering_bribery

Published Date: May 25, 2018