The following is part 3 of a 3 part series by Ryan Musser about Nigeria’s elections postponed to Saturday, February 23, 2019.

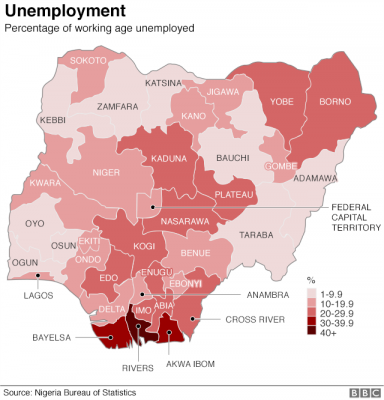

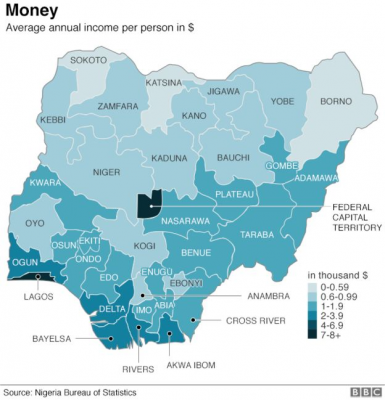

As Africa’s largest economy goes to the polls, its economic struggles lay heavy on the minds of many voters. The statistics are grim. Nigeria is the poverty capital of the world, more than half the population lives in poverty, and 60% of the urban population cannot afford the cheapest house. Unemployment is 23% nationwide, and is even higher in places like the oil-rich south, which ironically also has the highest average annual income per person. This suggests both high inequality and the fact that the oil industry is not delivering jobs.

Whereas Buhari is perceived to have the advantage on the issue of battling corruption, on the economy Atiku is the stronger candidate, providing more economic optimism, and he has indeed been running his campaign on economic issues. Of all the issues, the economy is where the two candidates diverge the most. Buhari’s preference is state interventionism, while Atiku puts his faith in the free-market.

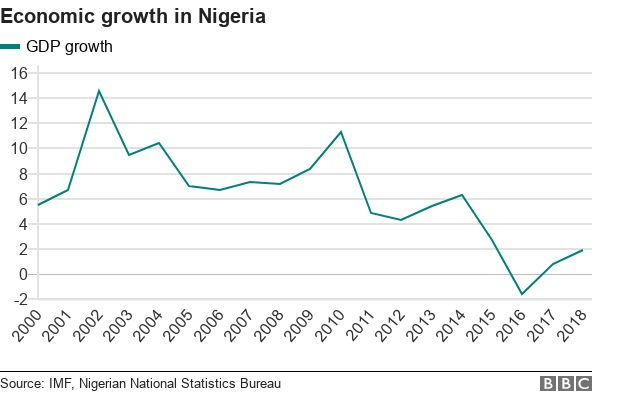

Early in Buhari’s presidency, the collapse in oil prices sent shockwaves through the Nigerian economy. Annual real GDP growth declined from 6.2% in 2014 to 2.7% in 2015, and by 2016 the economy recorded its first recession since 1991, with -1.5% GDP growth. Nigeria’s economy remains heavily dependent on oil, and as Nigeria’s exchange rate collapsed along with oil prices, the non-oil sector contracted by 0.2% in its worst performance since 1985. The Nigerian economy has continued to struggle since. Nigerians’ economic sentiment was trending positively before the 2016 oil crash, them plummeted, and has yet to recover, according to Pew Research. Nigeria is not oil-rich, but it remains oil-dependent.

Buhari has positioned himself as more of a pro-poor candidate, though the lagging economy has not done much to help those most in need. Atiku, the businessman, has positioned himself as the more pro-business candidate. Buhari’s tenure over the past four years has at times even been markedly anti-business. Investment has been hindered by a lack of clear policy guidance by Buhari’s administration, mismanagement of the naira by the central bank, and slow progress in economic reforms, according to risk advisors Ronak Gopaldas and Ryan Cummings.

The Buhari administration has also created a perception of significant business risk in Nigeria by seemingly attacking companies such as MTN. The South African telecom company has invested billions of dollars into Nigeria, paid $5.5 billion in taxes to the federal government, and created thousands of jobs in the telecom value chain, but the Nigerian government has gone after it on several occasions. In 2015, the government tried to extract a $5.2 billion fine from MTN for failing to disconnect phone lines during a registration exercise. After reducing that fine to $1.7 billion in 2016, the Central Bank later demanded $8.1 billion from MTN for having “illegally repatriated” money out of the country between 2007 and 2015, which was in violation of Nigeria’s “arcane and byzantine foreign exchange laws,” and it demanded $14 million from four banks for facilitating the transfers. Such heavy-handed extractions will only discourage foreign investment into Nigeria.

Buhari’s government has been inconsistent and incoherent in its message to investors. It has attempted to make it easier to do business in Nigeria with one hand, while frustrating its attempts with the other. Dianna Games, the CEO of Africa @ Work – a company dedicated to facilitating and improving business in Africa – aptly described this contradiction: “Despite efforts by the Buhari government to make it easier to do business, Nigeria has rather got a reputation for being heavy-handed with regulation [and for implementing ad hoc crackdowns on tax evasion and other structural problems], rather than putting in place sustainable policies and policing them properly. This has affected both foreign and local companies and had implications for perceptions of Nigeria as an investment destination”.

Atiku, on the other hand, has differentiated himself from Buhari on the economy and is generally seen as the pro-business candidate. He believes that the solution to Nigeria’s widespread poverty and endemic corruption is to give the private sector a greater role. While Buhari has said that he will focus on structural reforms to boost the oil and non-oil sectors, Atiku has promised more market-friendly policies to stimulate economic diversification. His campaign promises have included “sweeping economic reforms,” according to Capital Economics analyst John Ashbourne. Atiku wants to float the naira, appoint a new governor of the Central Bank, remove Nigeria’s cap on gasoline prices (which are among the lowest in the world), and privatize the state-owned oil company. In another move to increase Nigeria’s attractiveness for foreign investment, Atiku pledges to offer the lowest corporate income tax rate in Africa. Whereas Buhari has gotten cold feet on the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), Atiku has promised that he would do so (After leading the effort for years, Nigeria is one of the last countries on the continent not to have signed the agreement). The AfCFTA would provide a number of economic benefits to Nigeria. Atiku is decidedly free-market and has even expressed his admiration of Margaret Thatcher and her push to privatize industries.

While Buhari’s policies can be viewed as an economic nationalism and state intervention, Atiku’s are the ideological anthesis, seeking to unlock the private sector’s potential. “A win for opposition leader Atiku Abubakar would boost local markets, but he would probably struggle to enact his investor-friendly plans. Another term for President Buhari would prolong his growth-sapping policies,” concludes the economics research consultancy Capital Economics. Normally such free-market principles that enable businesses and entrepreneurs to thrive would be applauded. But given Atiku’s reputation for alleged corruption, there appears to be a dangerous trade-off. Columnist Olu Fasan sees worrying similarities to an earlier Nigerian ruler General Ibrahim Babangida, who allowed corruption and bribes to flourish in exchange for economic reforms. Though there is no chance of them winning, Nigerians should consider some of the platforms and proposals of third party candidates, such as Kingsley Moghalu, Oby Ezekwesili, Donald Duke.

Democracy and economic growth are intricately linked, and unfortunately, Nigerians don’t think that democracy is working for them, according to Pew Research. The best way to address political inequality is to increase economic equality, and the best way to address economic inequality is to create greater opportunity in the economy.

Conducting business in Nigeria remains difficult, however. Infrastructure severely hampers business, such as those in the manufacturing hub of Onitsha. Our partners that represent the private sector, such as the Nigerian Association of Chambers of Commerce, Industry Mines and Agriculture (NACCIMA) and the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and Industry (LCCI) have decried the effects of insecurity on business in Nigeria from conflicts such as the farmer-herder conflicts in the Middle Belt. The Brookings Institute warned in a recent report that economic reforms are crucial in order to reduce Nigeria’s oil dependency, and that Nigeria risks “a lost decade” of flat economic growth without reforms.

Doing Business Reforms

To attract investment, diversify the economy, and reduce Nigeria’s reliance on oil, the Buhari administration created the Presidential Enabling Business Environment Council (PEBEC) in July 2016. Led by Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, PEBEC aims to remove the critical constraints and bureaucratic bottlenecks to doing business in Nigeria, move Nigeria 20 places upwards in the World Bank Doing Business Rankings, and encourage more local and foreign investment. PEBEC is comprised of 10 ministers whose ministries, departments, or agencies (MDAs) have a direct impact on the business environment, as well as several other government representatives. The Enabling Business Environment Secretariat (EBES) works with the MDAs to implement PEBEC’s reform agenda.

In three years, PEBEC has enacted 140 reforms in the business climate, including:

- Issuing three National Action Plans and Executive Order 001 that contain far-reaching initiatives to be implemented by MDAs to improve transparency and efficiency in public service delivery

- Launching a PEBEC app that improves the processing of business documents, makes it easy for Nigerians to provide feedback and resolve issues on the service delivery of any government MDA, and contributes to identification of trends and tracking of issues

- Amending the Companies and Allied Matters Act of 1990, which is the largest business reform bill in the country in over 28 years

PEBEC is also working on the Omnibus Bill on Business Facilitation that would address bottlenecks for businesses by amending outdates laws with provisions in at least 30 existing commercial laws. This bill would aim to institutionalize business climate reforms already enacted by PEBEC and EBES, codify new rules and directives for agencies, amend provisions of the present legislative framework that have been identified as bottlenecks for business, and introduce new business-friendly provisions.

There was much celebration in 2017 when Nigeria jumped 24 places in the World Bank’s Doing Business Rankings, moving 169 in 2016 to 145 in 2017. But in October 2018, Nigeria moved back one place to 146. PEBEC is aiming to move Nigeria into the top 100 nations in Doing Business rankings by 2020.

Port Reform

One particular bottleneck in Nigeria’s business environment is the inefficiency of its seaports – a key aspect for importing and exporting, as well as diversifying Nigeria’s economy from oil dependency. Container traffic to Nigeria’s Apapa, Lagos port has dropped nearly 30% in the past five years. “Nigeria’s loss has proven to be Togo’s gain,” says Quartz’s Yomi Kazeem, “as the small West African nation doubles down on reform and investment plans to transform itself into a pivotal transit hub in the Gulf of Guinea.”

Since 2016, CIPE has been supporting the Nigerian private sector in engaging government stakeholders on port reform as a key factor for improving the business environment in Nigeria. In 2016, the Lagos Chamber of Commerce and CIPE published a report on the state of Nigerian ports and recommendations for improving the ports. The research found that Nigeria loses over N1 trillion (roughly $3.2 billion USD at the time) and 10,000 new jobs every year due to port inefficiencies, process failures, and corruption. As a result of these governance failures, companies in the Nigerian ports have to deal with .

The recommendations from the report were expected to be implemented within a few months In 2017, an executive order gave instructions on the implementation of some key activities at the Apapa Port that would improve operations. But the inefficiency of its ports has continued to cripple Nigeria’s economy. In 2017, in a World Bank indicator measuring the efficiency of ports, Nigeria was ranked number 183 out of 185 countries.

In 2018, CIPE supported LCCI and the Organized Private Sector (OPS) to follow up on LCCI’s original research from 2016 to capture the extent of reforms that have been made, highlight the present reality of the ports, identify gaps in the implementation of previously recommended policies, and engage PEBEC and other relevant authorities on updated recommendations. The updated 2018 report found that Nigeria is currently losing N2.5 trillion ($7 billion USD) of corporate earnings on annual basis due to port inefficiencies, with a drag of about 3% on Nigeria’s GDP. The updated report identified “considerable improvement in the condition of facilities and activities at the Ports” yet also found a “worrisome level of deliberate resistance by some MDAs to implement/enforce enabling regulations including the 2017 Presidential Executive Orders relating to the ports. Fight for supremacy, conflict of interests among the MDAs and revenue ambitions that conflicts with trade facilitation among the MDAs is widespread.” The report concluded that “the success of the ongoing reforms in the ports is largely predicated on the continued buy-in and political will of the Presidency and PEBEC.”

After the release of the report, OPS and LCCI met with a number of government officials, including The Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment and the Vice-Chairman of PEBEC, Dr. Okechukwu Enelamah. They continue to work with government on the crucial job of reforming Nigeria’s ports, which is crucial for diversifying Nigeria’s economy and creating more economic opportunity for all Nigerians.

But meanwhile, businesses across Nigeria remain weighed down by multiple taxes and levies, lack of electricity, and lack of access to credit. Economist Nonso Obikili told Quartz, “The reform agenda needs to be driven down to state and local government institutions.” He said that the reforms must “move beyond the bureaucracy of doing business, and push on infrastructure, human capital, security, and other institutional improvements which are also key for competitiveness.”

CIPE has been doing precisely this, working with business coalitions in a number of states in the Middle Belt. We helped them to develop business agendas for policy reform at the state level for Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Enugu, and , which they then used for engaging government to advocate reforms. During this election season, we supported these business coalitions in organizing gubernatorial debates in states like Niger, Kwara, Nasarawa, and Plateau in order to infuse electoral discourse with economic issues affecting SMEs in states throughout Nigeria.

As Nigerians head to the polls on Saturday, they face a hard choice. According to Olly Owen, an African studies professor at Oxford University, Buhari and Atiku each appeal to two different Nigerian yearnings: clean government and economic opportunity. Unfortunately, each candidate appeals to only one of those desires. “People are sick of corruption,” Owen says, but they are also “very entrepreneurial”.

“If Buhari wins, expect more of the same statist, interventionist and anti-business policies,” says Nigerian columnist Olu Fasan. “And if Atiku wins, expect a lot of activities around economic, political and institutional reforms and a radical free market approach, but also a brash, laissez faire attitude!”

Whoever wins, however, the business community in Nigeria has a role to play in improving democratic and economic opportunity for all. The private sector can do so by remaining engaged with government, advocating solutions to reduce economic barriers, tackle corruption, and increase economic opportunity for all Nigerians and to ensure that democracy is working everyone.

Ryan Musser is a Program Officer for Africa at CIPE.

Published Date: February 15, 2019