The following is part 1 of a 3 part series by Ryan Musser about Nigeria’s elections postponed to Saturday, February 23, 2019.

This Saturday, the most populous country and largest economy in Africa heads to the polls for national elections in Nigeria. According to Jibrin Ibrahim of the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), over 23,000 candidates are contesting for seats in the elections.

In the previous elections in 2015, Nigerians witnessed for the first time a democratic and peaceful transition of power to an opposition party when former general Muhammudu Buhari successfully led a coalition of opposition parties collectively known as the All Progressives Congress (APC) to defeat the incumbent president, Goodluck Jonathan of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). The same issues remain the focal point as before: corruption, the economy, and insecurity. Will Nigerians give President Buhari and the APC a vote of confidence or demand change? And will the elections be seen as credible or disrupted and tainted by a number of challenges?

In this election, Buhari is being challenged by businessman Atiku Abubakar, the PDP candidate who served as vice-president from 1999 to 2007 under president Olusegun Obasanjo, along with scores of other third-party candidates. Before the 2015 elections, numerous politicians defected from the incumbent PDP to the opposition APC, including Atiku, former president Obasanjo, and President of the Senate Bukola Saraki. Now, in the lead-up to this year’s elections, dozens of politicians have defected from the APC back to the PDP, again including Atiku, Obasanjo, and Saraki. Meanwhile, more PDP politicians have again defected, as politicians jockey to be on what they think will be the winning team.

Such an act of musical chairs has been a challenge to democracy in Nigeria and reflects the state of Nigerian politics. Discourse and electioneering have generally lacked a substantive debate of issues and policies and focused more on being on the winning team. Political power has often been considered the easiest route to wealth in Nigeria, and as a result, elections have been hotly contested since the end of military rule in 1999. But the intense contests do not necessarily produce the ablest leaders with the best policy prescriptions. “The two parties are essentially elite machines for winning elections rather than advancing a policy agenda, and politicians move easily from one to the other depending on personal expediency,” explains former US ambassador to Nigeria John Campbell.

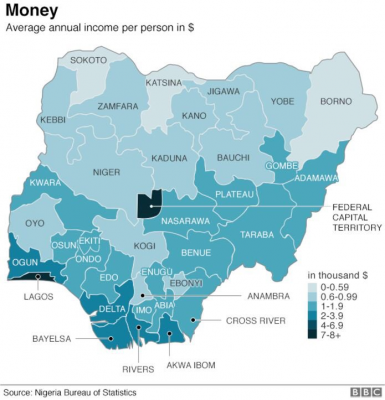

To help the business community infuse substantive discussion into election discourse, CIPE worked with local business groups in Nigeria’s Middle Belt to host a series of debates during election season. These debates aimed to bring Nigeria’s business environment reform agenda to the state level, and discuss issues of insecurity, lack of infrastructure, finance, and burdensome administrative procedures that plague businesses in states like Niger, Kwara, Nasarawa, and Plateau.

Regionalism plays an important role in Nigerian politics both on a national and sub-national level. Constitutionally, to win the presidency, a candidate must obtain at least 25% of the votes in at least two-thirds of Nigeria’s states (24 of the 36 states) as well as a majority of the national vote. Informally, Nigerian political elites also agree to concepts of zoning and rotation to manage identity-based conflicts. This includes an expectation that the presidency will rotate between the north and the south every eight years (similar agreements occur on the sub-national level). As a result, both Buhari and Atiku hail from the north, while their vice-presidential running mates come from the south.

While Nigerian democracy continues to strengthen between every election, there are reasons to be concerned with this election. There are a number of security issues across the country that threaten peaceful elections and the stability of the country. The International Crisis Group sees the risks of violence to be highest in six states: Rivers, Akwa Ibom, Kaduna, Kano, Plateau, and Adamawa. The risk of violence is often due to local political dynamics and rivalries involving a mix of factors that include “an intense struggle between the APC and PDP for control over states with large electorates, vast public revenues or symbolic electoral value; local rivalry between former and incumbent governors; tension resulting from ethno-religious or herder-farmer conflict; and the presence of criminal groups that politicians can recruit to attack rivals and their constituents.”

While Nigerian democracy continues to strengthen between every election, there are reasons to be concerned with this election. There are a number of security issues across the country that threaten peaceful elections and the stability of the country. The International Crisis Group sees the risks of violence to be highest in six states: Rivers, Akwa Ibom, Kaduna, Kano, Plateau, and Adamawa. The risk of violence is often due to local political dynamics and rivalries involving a mix of factors that include “an intense struggle between the APC and PDP for control over states with large electorates, vast public revenues or symbolic electoral value; local rivalry between former and incumbent governors; tension resulting from ethno-religious or herder-farmer conflict; and the presence of criminal groups that politicians can recruit to attack rivals and their constituents.”

As Idayan Hassat, the executive director of the Centre for Democracy and Development explains, security risks across the country include the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast, the herder-farmer conflict in the Middle Belt which is actually more deadly than Boko Haram, armed banditry in the northwest, Biafran separatists in the southeast, and political thugs working with political figures to intimidate citizens and rig votes particularly in the South-South zone. Hassat believes that the most potent of all the threats, however, is partisanship among security forces who are supposed to ensure peaceful elections across the country.

Concern about the partisanship of security forces, and vote-rigging that comes along with it, was reinforced with the 2018 Osun state elections. Its flaws could be foretelling of the national and state elections coming up. In September 2018, Osun state held special off-cycle elections for governor. What was once expected to be an easy win for the incumbent APC resulted in a surprisingly close election in which the PDP candidate got more votes, but the election was determined inconclusive by Nigeria’s election management body. A highly flawed re-run was then held that resulted in the APC candidate winning. The process of the re-run provided serious concerns of election mismanagement and rigging. The Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room, a broad platform of 60 civil society organizations, released a statement that the election was “heavily policed” with security forces, including the army, that “created heavy tension and apprehension among voters.” The Situation Room noted “reports of political thugs and hoodlums being used to intimidate voters” and “incidences of violence and gunshots around some of the polling units and attacks against opposing political sides with supporters of a particular party being prevented from voting.” The group concluded that “the lapses in the Osun re-run elections has put a serious question mark on the electoral process and raises concerns about the forthcoming 2019 Nigeria general elections.” Throughout the election campaign, the PDP has been particularly vocal in its warnings of vote rigging by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and security forces.

Further deepening suspicions of vote-rigging, on January 25 President Buhari suspended the Chief Justice of Nigeria, Walter Onnoghen, due to accusations of failing to declare his assets. Buhari claimed to be acting on an order from the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT). Buhari replaced Onnoghen with an acting chief justice, Tanko Muhammad. This is worrisome because, as the head of Nigeria’s independent judiciary, Onnoghen was expected to oversee any electoral disputes in the upcoming February 16 election. Buhari apparently did not follow the provisions in the constitution that provide some checks and balances from either the Senate or the judiciary. Although Nigeria’s judiciary is seriously compromised, the courts have in the past played a stabilizing role in the electoral conflict. Buhari’s action casts doubts about the rule of law in Nigeria and causes many to see this as “a calculated attempt to gain some electoral advantage should an election petition between the president and the main opposition party end up in the Supreme Court.” Atiku called the move an act of dictatorship, the Nigerian Bar Association called it an “attempted coup,” and the US Embassy said that it “undercuts the stated determination of government, candidates, and political party leaders to ensure that the elections proceed in a way that is free, fair, transparent, and peaceful – leading to a credible result.”

In addition to vote rigging and voter intimidation, however, vote-buying remains another threat to legitimate and credible elections. To improve the management and integrity of elections, in 2015 biometric voter-card readers were introduced by INEC. These card readers have “reduced the broad-daylight rigging of elections,’’ says Idayat Hassan. “The trend now is to buy votes, disrupt elections in opposition strongholds, which often leads to an inconclusive election.” Just this past Sunday, days before the election, President Buhari warned that Nigeria’s anti-graft agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, has raised concerns that laundered money could be used to buy votes.

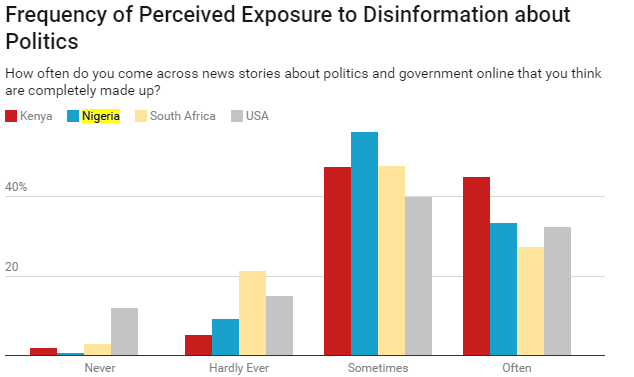

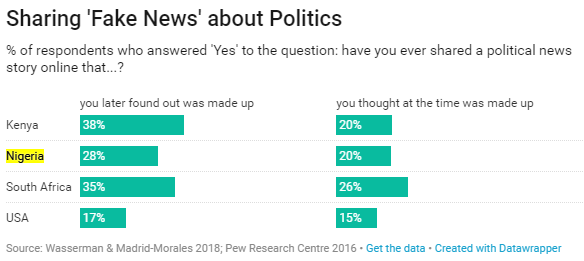

Another threat to these elections is the pervasive presence of fake news. While fake news is not new to Nigerian politics, this phenomenon has reached new heights, says Idayat Hassan. With the widespread adoption of social media, particularly Facebook, Twitter, and Whatsapp, it is making it easier for fake news to spread and gain traction, even resulting in people being killed. Nearly one-third of Nigerians have reported sharing news they later found was made up, according to a study by Nieman Lab. Most famously this cycle has been an outrageous yet persistently shared story that President Buhari died from an illness and is being impersonated by a Sudanese clone named Jubril. This story started from a Biafra secessionist group and eventually started going mainstream. The government’s poor communication about Buhari’s 150-day medical leave in London certainly contributed to the story’s ability to gain traction. These fake news stories serve as another means to garner more votes, divide the electorate, or suppress votes for one’s rivals, notes Idayat Hassan. In response to this trend, 16 Nigerian newsrooms have been collaborating to debunk fake news through the fact-checking project CrossCheck Nigeria.

Another threat to these elections is the pervasive presence of fake news. While fake news is not new to Nigerian politics, this phenomenon has reached new heights, says Idayat Hassan. With the widespread adoption of social media, particularly Facebook, Twitter, and Whatsapp, it is making it easier for fake news to spread and gain traction, even resulting in people being killed. Nearly one-third of Nigerians have reported sharing news they later found was made up, according to a study by Nieman Lab. Most famously this cycle has been an outrageous yet persistently shared story that President Buhari died from an illness and is being impersonated by a Sudanese clone named Jubril. This story started from a Biafra secessionist group and eventually started going mainstream. The government’s poor communication about Buhari’s 150-day medical leave in London certainly contributed to the story’s ability to gain traction. These fake news stories serve as another means to garner more votes, divide the electorate, or suppress votes for one’s rivals, notes Idayat Hassan. In response to this trend, 16 Nigerian newsrooms have been collaborating to debunk fake news through the fact-checking project CrossCheck Nigeria.

While these elections are hotly contested and supporters of each candidate may be intense in their fervor, many Nigerians also remain apathetic about candidates that offer few new solutions to Nigerians’ problems, particularly for young people. Both candidates have serious flaws. Bloomberg cynically describes the choice as between a former dictator and alleged kleptocrat. Business Day columnist Olu Fasan says it’s between a pious socialist or a brash, amoral liberal. The Economist says that “both candidates are boringly familiar to voters.” Atiku has been in every election since 1999 and Buhari in every one since 2003. Both men have had three failed presidential runs. Buhari succeeded on his fourth. Will Atiku as well?

With a majority of the electorate under 35 years old, this is the first election since the Not Too Young to Run Campaign that successfully lowered the age requirements to run for elective positions in the House of Assembly and House of Representatives, the Senate, governorship, and presidency. An incredible 1,515 young Nigerians between the age of 18 and 35 are running for seats in the National Assembly. And yet of the two main presidential candidates, Atiku at 72 years old is considered the younger candidate. Nigeria is set to get another president who is a septuagenarian man. Both candidates’ vice-presidents seem to be of a younger generation, and yet they are still 61 and 57 years of age. Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, being more youthful and energetic than Buhari, has played a much larger and more public role in campaigning and running the country than one would normally expect of a vice presidential candidate. He’ll likely play an even bigger role next term if elected, effectively becoming the public face and voice of the president.

In past elections in Nigeria, political campaigns and electioneering have been dominated by patronage and godfatherism, power positioning, and ethnic and regional identity more than ideological stances. Some observers think that this year’s election campaign is starting to take on a more policy and issue-based approach than previous elections, as noted recently by panelists at a recent event on Nigeria hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The third-party candidates and the reach of social media have increased the appetite and avenues for dialogue and debates about policy issues.

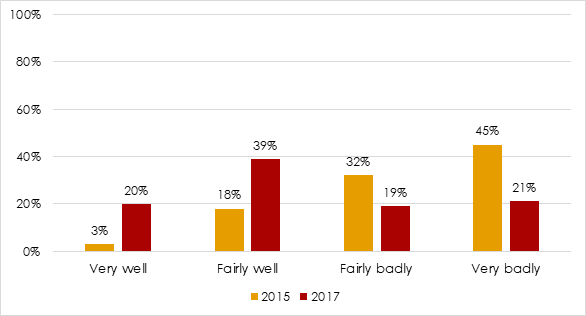

In 2015, Buhari rose to power on a campaign of fighting corruption and establishing security. Many skeptics challenged his record as a former dictator, prompting him to promise his renewed appreciation of democratic values and institutions, calling himself a “converted democrat.” Four years later, however, many Nigerians are disappointed in his performance. Security remains fragile or elusive in several parts of the country – violent clashes between herders and farmers have increased in the Middle Belt, Boko Haram has seen a resurgence in the northeast, armed banditry is prevalent in the northwest, and a secession movement has reignited in the southeast. His human rights record has come under attack as it appears that the democratic space is closing in the country. Meanwhile, clear action has been taken on the anti-corruption front, with general approval by Nigerians. According to a 2017 Afrobarometer survey, 59% of Nigerians polled said the government is performing “fairly well” or “very well” in fighting corruption. In 2015, only 21% thought so. But some critics argue that his anti-corruption campaign has been politicized and focused on Buhari’s political enemies.

Meanwhile, one of Buhari’s greatest criticisms is his mishandling of the economy. The Buhari administration does have some economic achievements to point to. The Financial Times summed them up:

The administration has defended its record, touting achievements that include a rise in foreign reserves; a current account surplus; significant power, road and rail infrastructure investment; and a drop in inflation. Its policies have helped Nigeria move up 24 positions on the World Bank’s ease of doing business index, from 169 in 2016 to 145 in 2017. Vice-president Yemi Osinbajo is also widely admired in the business community.

Even so, Nigeria has struggled economically for much of the Buhari years. Chris Ngwodo, a political analyst in Nigeria said, “If the opposition was to ask the average Nigerian, ‘are you better off than you were four years ago?’ The answer would be no.”

When Buhari rose to power in 2015, he represented change – a break from the past. But February’s elections will provide the electorate an opportunity to decisively judge Buhari on the past four years. A Buhari vote represents approval of the status quo. For many Nigerians, that’s not enough, considering that Nigeria has now overtaken India as the country with the largest amount of people in the world living in extreme poverty.

But does Buhari’s main contender Atiku Abubakar offer much of an alternative? Atiku served as vice president for Olusegun Obasanjo under the PDP, the party that represents the past that voters rejected in 2015 in hope for change. But Atiku hopes that he can attract some of Buhari’s former supporters, particularly educated urban youth who are struggling in the current economic situation.

As we enter the final stretch, these elections are largely about the same issues as the 2015 elections: corruption, lack of economic opportunity, and increasing insecurity. It remains unclear who Nigerians think will be best to deal with these challenges in the next four years. Who will be better for democracy and economic opportunity in Nigeria? No matter who wins the presidency, for Nigeria to move forward, it is crucial that Nigeria’s political leaders engage civil society, including the business community, to ensure that policies are enacted that make Nigeria an easier and more secure place to do business, create economic opportunity for all Nigerians, and allow Nigerians to participate in the democratic process from Lagos to Maiduguri to Port Harcourt to Sokoto and everywhere in between.

Ryan Musser is a Program Officer for Africa at CIPE.

Published Date: February 13, 2019