Women’s economic empowerment (WEE) is now a global development, economic, and national security priority. Donors and implementers alike acknowledge that women are key to the development of sustainable livelihoods, reductions in poverty, as well as peace-building. Women typically invest as much as 90% of their income into their families compared to 30-40% by men. Women’s spending also tends to be focused on improving the wellbeing of their children. As a result, the families of employed and entrepreneurial women are generally better-fed, healthier, and more well-educated. When empowered women participate in peace processes, the resulting agreement is 35% more likely to last at least 15 years. Additionally, women own close to 10 million of the world’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and SMEs overall account for almost 80% of jobs around the world; therefore, increasing the viability of women-owned businesses boosts job creation.

Implementers are recognizing that doing WEE only at the population or household level is not enough. Change will be incremental, not catalytic, until we create an inclusive enabling environment for women in the economy. This includes policy reforms expanding economic resources controlled by women in the broader community, such as those developed by women business owners and entrepreneurs, which can lay the groundwork for collective action and problem-solving. Indeed, scholars increasingly recognize that empowered women often lay the basis for most reform movements.

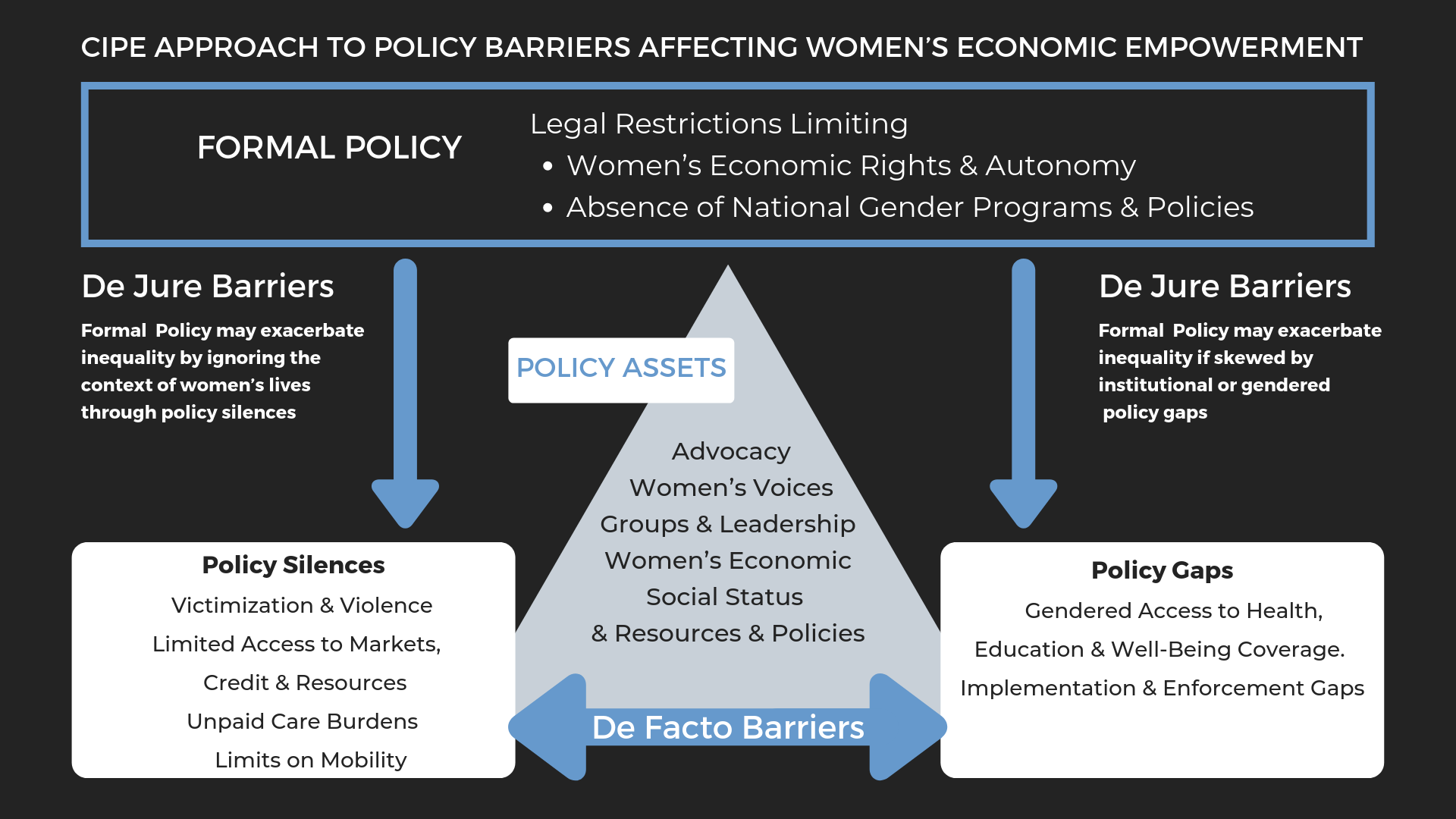

CIPE’s approach to policy reform goes well beyond adopting new public policies or the removing of policy barriers. As a world leader working with private sector groups on policy reform and as an innovator in women’s economic empowerment, CIPE believes that effective policy reform includes addressing policy gaps and silences as well as improving policy implementation in ways that build upon women’s policy assets (See Figure). Barriers to women entrepreneurs and women-owned businesses can include formal policies, such as legal restrictions that limit women’s economic rights and autonomy, as well as the absence of national gender programs and policies. These policy barriers can be understood as including formal (or de jure) legal barriers, as well as informal (or de facto) policy silences and policy gaps.

CIPE’s experience in designing and implementing WEE programming in more than 60 countries has yielded five key lessons for effective evidence-based policy reform.

1. Use a Gender Lens.

Gender-neutral policies and gender equity alone may fail to empower women because they fail to take account of the fact that men and women live different lives. These policies presume women will be autonomous, unencumbered individuals. In contrast, a gender lens ensures that reform is locally-owned and data-driven in ways that address the local context, help you see what is not seen, properly value what is seen, and even out what may be in flux due to changing gender roles and norms. In other words, a gender lens can help in assessing different expressions of power which include power over (hierarchies, control, discrimination), power to (individual agency), power within (personal assets and self-confidence), and power with (women’s groups and collective action). In addition to considering factors such as violence against women, legal and policy barriers, or acts of discrimination, a gender lens also considers how women may approach things differently or receive them differently than men do in a society. Women may have differing levels of awareness of how their gender may structure their roles and opportunities.

a. In El Salvador and Honduras, CIPE’s barrier assessment conducted with Women and Girls Empowered (WAGE) Consortium partners American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative, Grameen Foundation, and Search for Common Ground found that women business owners needed more than micro-finance to scale their businesses but were excluded from bank loans due to gender norms of machismo. The assessment also found that insecurity affected women’s access to public space and mobility to business meetings as well as business locations.

b. In Serbia, CIPE supported a mentorship program that purposely worked only with women, drawing on input from a local partner organization, indicating that male entrepreneurs in Serbia often do not understand the nuances and specific challenges that women business owners face. The program matched 27 women starting out in business with established women business owners to enhance the strategy, marketing, and operations of these new enterprises.

Asking the women, working with local partners and ensuring that there are local champions and stakeholders is key to targeting reforms that matter.

2. Address Policy Gaps.

Formal policy may exacerbate inequality if skewed by institutions that do not include women, if there are gendered policy gaps which treat men and women as having equal opportunities, or when there are implementation and enforcement gaps, either through poor policy design, bureaucratic and civil service incompetence, or corruption. Policy gaps are also evident where there are differences between men and women in access to good health, education and overall well-being. These gaps mean that women have structural disadvantages in life such as lower literacy rates that undermine their ability to function in society and to become entrepreneurs. While many developing countries have adopted national gender policies, implementation gaps remain. Enabling regulations may not be adopted, resources may not be budgeted, or the personnel responsible for implementation may lack the needed skills, training, or interest. Governments can take a carrot or a stick approach to implementation, and there can be gaps at different levels of government or in different regions based upon local cultural norms.

- In Zimbabwe, despite the 2009 Constitution and 17 new laws providing rights to women, implementation gaps remained. CIPE addressed these by improving the capacity of a coalition of 35 women business associations to participate in the governance process, informing women in business about their rights and economic opportunity, and developing relationships and engaging the government on issues affecting women throughout Zimbabwe.

- In Papua New Guinea, CIPE’s entrepreneurship training includes financial literacy – a critical need given the education gaps and a skill that underpins businesses’ capacity to succeed.

- In Turkey, CIPE’s business training works with home-based food businesses, which is how many women entrepreneurs start given their double responsibilities as caregiver and entrepreneur.

The key is ensuring that de jure policies are in fact de facto policies that are fully implemented by working with women where they are.

3. Address Policy Silences.

Formal policy may exacerbate inequality by ignoring the context of women’s lives (e.g., domestic violence and family responsibilities) through policy silences. These can include victimization and violence, limited access to markets, credit and resources, unpaid care burdens and limits on mobility.

a. In Bangladesh, CIPE’s program helped unlock $95 million in commercial loans for more than 10,000 women business owners, not only by working with the Central Bank to introduce new rules on the share of commercial banks’ portfolios allocated to women borrowers, but also by introducing the requirement that banks establish loan desks staffed by female loan officers trained in gender sensitivity.

b. In Jordan, CIPE and one of its association partners sought to address challenges that aspiring women entrepreneurs faced due to limits on mobility and child care burdens. The project contributed to securing new rights for women entrepreneurs to obtain licenses for home-based businesses.

The key is to address policies that can be both public and private-sector based in nature.

4. Build on Women’s Assets.

Personal and business assets can increase resilience for aspiring entrepreneurs that enable them to surmount adversity. Personal assets can include confidence and entrepreneurial risk-taking skills, while business assets can include membership in business associations that provide for collective action. It is through organizing and collective action that access to institutions is increased.

a. CIPE has built the capacity of women’s business associations worldwide, ranging from a regional initiative in South and Southeast Asia, including Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nepal and Sri Lanka to specific in-country initiatives in Jordan, Nicaragua, Zimbabwe, among others.

b. CIPE has been a leader in establishing mentoring programs for women, both among individual entrepreneurs in Nicaragua, Turkey and in Papua New Guinea and among women’s business associations across Asia.

c. CIPE has found that creating Women’s Business Agendas (WBAs) can be a vital advocacy, organizing and awareness raising tool that creates consensus, sets legislative priorities, and communicates to policymakers using public-private dialogue in numerous countries, including Bangladesh, Nigeria, Jordan, Pakistan and Nicaragua.

The key is to work with women’s organizations, business associations, and chambers to increase women’s strength and resilience and ensure that women entrepreneurs have a voice in shaping laws and policies that govern them.

5. Promote Business Resiliency.

Business resilience is essential to community resilience. For communities to recover and grow after a disaster or other crisis, businesses must be able to continue to provide jobs and serve the community.

a. In Turkey and Papua New Guinea, CIPE has developed resources that serve women and provide a safe space where they can develop and grow their businesses.

b. In Nepal, with CIPE’s support, a business association for women entrepreneurs successfully advocated in Parliament the passage of a long-delayed agricultural bill containing a variety of measures designed to help women-owned agribusinesses recover from a devastating earthquake and build more resilient livelihoods.

The key is working to ensure that women entrepreneurs have an appropriate business plan and strategy that is market-driven and have access to resources that enhance their business resiliency.

These five keys to women’s economic empowerment and policy reform are crucial to leveling the playing field for all women. Policy reform too often targets formal rights such as constitutional, legal and political rights. Women’s empowerment is too often focused narrowly on women’s legal inferiority, with roots in marriage and family law that in many countries limit women’s rights to property and contracts.

Using a gender lens goes beyond de jure status of on-paper equality and recognizes, as political scientist Thomas Dye famously said, that public policy is “whatever governments chose to do or not to do.” As such, policy silences occur when governments fail to act on a problem (Dye, Understanding Public Policy 1984, 5th edition, page 1).

For women, policy silences are as important as what government authoritatively decides to do.

Two major questions that are answered differently in different contexts and at different times in history are: What is the appropriate policy space for women’s issues? Is there public will or political will to take actions? In part, the answers depend on what is perceived as a social problem. Women’s organizing and capacity building can shape this perception.

Women business owners and entrepreneurs are distinctive in that they bring their own passion to innovate and problem-solve and their own business resources to the policy reform table. Equal participation of women in the economy provides critical support to policymakers, including elected women, strengthens free markets and underpins democratic institutions by organizing and amplifying the voice of private enterprise.

Published Date: October 09, 2019