Customers everywhere are complaining about empty shelves, while retailers explain that supply chains are tangled or broken.

Yet there are ways that government and private sector could work together to improve the situation. For example, by making cross border trade simpler by reducing the paperwork that traders must submit to different government agencies to be allowed to import and export goods.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the average international trade transaction involves anywhere from 20–30 different parties, 40 documents, 200 data elements (30 of which are repeated at least 30 times) and the re-keying of 60–70% of all data at least once. It is hard to find any other government service that requires such a vast amount of paperwork.

Additionally, trade analysts point out that one key reason why many small and medium enterprises are not active players in international markets has more to do with red tape than tariff barriers (which have consistently gone down for the last 30 years after multiple rounds of WTO negotiations). For the majority of SMEs, the bureaucracy associated with international trade is simply too complex and mysterious to make foreign markets attractive.

That’s why trade facilitation is so vital. The World Trade Organization is addressing the problems head on through the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), a legally binding agreement approved by 154 countries that entered into force on Feb 22, 2017. CIPE supports the implementation of TFA through the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation.

Among many other things, the TFA requires member countries to create national trade facilitation committees (NTFCs) whose ultimate goal is to eliminate red tape and simplify processes through public-private dialogues. Unfortunately, and as we approach the 5-year anniversary of the TFA, it is unclear to what extent these committees have advanced the trade facilitation agenda.

On the bright side, the committees have broken the silence and opened an (imperfect) dialogue between governments and traders.

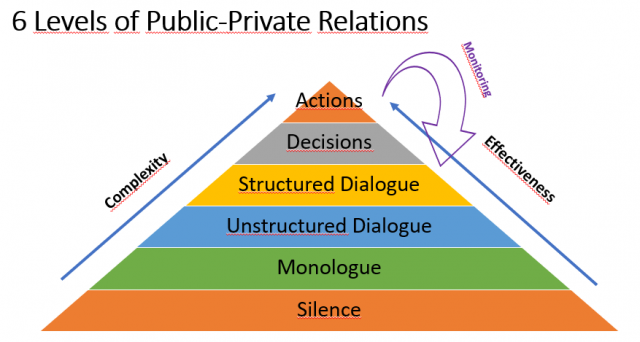

To help us better understand the level of sophistication in public-private dialogues, we have created the following conceptual framework which summarizes the different stages that we see:

Level 1: Silence. Although NTFCs are doing their part to facilitate communication, this is the most basic level, where none of the stakeholders communicate with the other. This level is characterized by government and/or private sector indifference towards one another. Border agencies (not just customs, but also agriculture, health, and immigration authorities) act independently from the private sector and hardly do anything to communicate new laws, new procedures or changes to existing processes.

Level 2: Monologue. Communication here between government and private sector is one directional and typically led by border agencies that limit themselves to the publication of new rules and processes through official gazettes. There is little room for the private sector to provide comments or suggestions.

Level 3: Unstructured dialogue. Again, thanks to the work of NTFCs, this is probably the most common level in public-private dialogues. This type of dialogue is:

- Basically a platform to voice accusations and complaints.

- Based on generalities and anecdotes. Extraordinary claims are presented without any evidence.

- Plagued with vague terms, issues unexplained and complaints not followed up on.

- Not representative of the entire trading community. Key stakeholders are absent from the discussions.

Level 4: Structured Dialogue. We have now reached the productive zone of our diagram. It is essential to unlock this level to change something and get results. The main characteristics on this level:

- A focus on specific problems.

- Discussion is based on a rigorous problem diagnosis and data is presented to back up claims.

- The emphasis and spirit of the discussion is on collaboration and the pragmatic identification of solutions.

- Meetings take place regularly, with a large representation of all stakeholders.

We must emphasize the importance of focusing each discussion on specific topics. For example, when we speak of foreign trade we are traditionally talking about imports and exports. In reality, it is far more complex than that. There are many types of import and exports with different procedures involving many different agencies. Hence centering the dialogues on specific topics is essential to get results.

Finally, it is important to note that this level can only be unlocked when border agencies accept the notion that the private sector can indeed be a partner and a force multiplier. If government sees traders as the enemy, or simply as the regulated party, all efforts to reach this level will be futile. A successful public-private dialogue rests on the notion that both parties respect each other and genuinely believe that they will be better off by collaborating with one another.

Level 5: Decision Making. Dialogues are pointless unless they lead to decisions. We can only move forward when we make a decision. The first objective of a public-private dialogue is to decide what and how something is going to change. Inertia is one of the strongest forces in the universe and the “do-nothing” syndrome is an epidemic that exists across public institutions. Recall the famous organizational imperative of Warren Buffett: “As if governed by Newton’s First Law of Motion, an institution will resist any change in its current direction.”

Excellent NTFCs are characterized by their ability to make decisions on specific issues. Once a problem is properly identified, stakeholders make a decision to solve it.

Level 6: Actions. We have already arrived at the most complex yet most rewarding level. Although decision making is in and of itself an achievement, taking action still remains the most critical element in our framework. If a picture is worth a thousand words, one action is worth a million words. Our nations are plagued by agreements and good intentions that never come to fruition. Just because a decision is made doesn’t mean that it will be carried out. In this phase it is of utmost importance to ensure that all stakeholders have the human, technical, and financial resources to embark on this process of change. The private sector can help the authorities move forward with the NTFC decisions by contributing expertise, data, people and even financial support if needed.

Progress never happens in a straight line, but rather in an iterative manner. Therefore, we always recommend that NTFCs appoint a task force of public and private sector officials to monitor the implementation of those decisions and regularly report back to the NTFC and the heads of the government agencies involved:

- The creation of a public-private monitoring team sends a strong message of commitment to the reform.

- We ensure alignment with the spirit of the decision.

- We get feedback from users that will help calibrate the reform as it is implemented.

Every organization must have some mechanism to regularly assess, review and get rid of the processes that no longer make sense, and NTFCs, if properly managed, are uniquely positioned to be part of that mechanism. As former American cabinet secretary John Gardner put it, “An organization must have some means of combating the process by which people become prisoners of their procedures. The rule book becomes fatter as the ideas become fewer. Almost every well-established organization is a coral reef of procedures that were laid down to achieve some long-forgotten objective.”

At CIPE, and through the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation, we have a team of dedicated trade professionals committed to modernizing border agencies and creating an environment where international trade is seen as a right and not a privilege.

This piece first appeared at RealClearMarkets.

Published Date: January 27, 2022