The amount of effort the South Korean government puts into youth entrepreneurship is tremendous. Youth entrepreneurship is seen as a solution to combat the high youth unemployment rate. Since Moon Jae-in’s administration began in 2017, the government has invested close to $700 million USD to implement business model competitions and youth entrepreneurship programs. However, as pointed out in part one of this two-part series, these government programs are not motivating students enough to become entrepreneurs.

Three main characteristics of Korean society continue to keep youths from becoming entrepreneurs: 1) the misallocation of resources to the business model competitions; 2) the lack of practical entrepreneurship education; 3) and the domination of the Korean market by big conglomerates, or chaebols. Korean society can improve its low youth entrepreneurship rate only when these problems are addressed in policy-making.

First, the government budget invested in business model competitions is not focused on business at the stage of realization. Seventy-eight percent of government support is focused on working with entrepreneurs to develop their business ideas at the initial stages. Programs that support businesses more than three years old take up only 16% of the whole budget even though they are the ones that are most vulnerable due to lack of finance. The time when a business is from three to seven years old is largely called the “death valley” of business. Death valley is especially more difficult for Korean startups when comparing their survival rate to those in United States. In the United States, 43% of establishments still survive by their fifth year anniversary. In Korea, however, only 27.5% of startups maintain their business for five years or more. This is due to risk-averse attitudes of Korean banks along with a relatively low percentage of venture capital investment. In 2016, Korean venture capital makes up only 0.13% of GDP, whereas the number is 0.37% in the United States, and 0.28% in China.

Too much of the government’s budget is used for supporting ideas that are not tested in the market. Korean news media have found out that government funded programs actually support many ‘zombie startups’ that take support from the government without continuing to run a business. These companies make multiple bank accounts for several programs or register a fake address to prove that they have an office. There are even services that receive commissions for writing business plans to win government funding. These examples show that government budget is misallocated to support the wrong business. Zombie startups or commissions business would not contribute to promoting youth entrepreneurship. To prevent these loopholes, there should be a stronger monitoring process for business model competitions, as well as effort to decrease the number of repetitive programs. More emphasis should be put on supporting startups that are trying to scale up instead.

There is another sector that needs to be re-examined: entrepreneurship education. The Korean government has placed strong emphasis on entrepreneurship education since 2015. However, the way entrepreneurship education is structured at most universities is not helpful in gaining the practical knowledge for starting a business. The Korean Ministry of Education recognizes a course as an ‘entrepreneurship’ course when 1/3 of class time contains lectures relevant to operating a business. This means anyone with a high position in a conglomerate can give a lecture on topics irrelevant to starting a business, but the course would still be included in the “entrepreneurship” category of class offerings. Seventy-nine point three percent of entrepreneurship training is also lecture-based. As a result, current entrepreneurship education lacks diverse course contents. According to a report by the Korean National Assembly Research Service, current entrepreneurship courses are heavily focused on the early stages of starting a business. Most of the courses only cover introductory topics, such as: “Entrepreneurship and Business”, “Theories on Entrepreneurship”, and “Writing a Business Plan”. Furthermore, these courses are only accessible to university students majoring in business. According to a survey done by Korean Research Institute for Vocational Education & Training, 41.2% of students wanted courses to be more connected with real business. One in five students wanted more diverse courses. In short, even kids who attend business school feel ill-prepared to start.

As the Korean job market grows increasingly competitive year after year, Korean youths show risk-averse attitudes when choosing a career path. They prefer public sector over private sector even though working for the private sector is much more profitable. Youths are not aware of how to start a business, not to mention the value of entrepreneurship. The Ministry of Education should put a strict standard in acknowledging entrepreneurship courses. Furthermore, the current system must improve its content to include direct experience for students to develop their ideas and test them in the market within the boundary of universities.

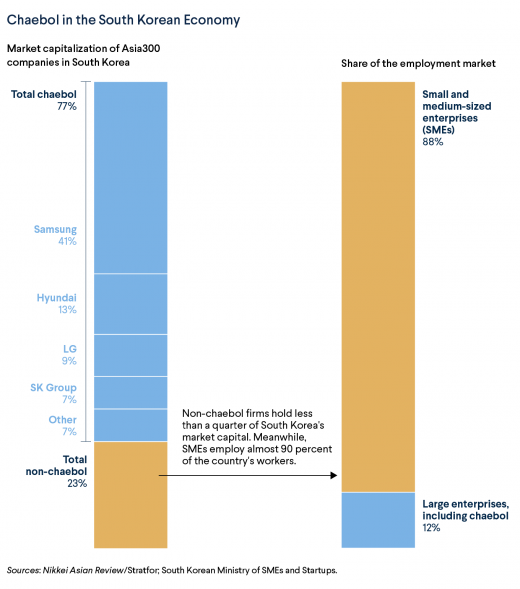

In addition to such misallocation of resource or lack of practical education, there is a bigger barrier in starting a business; severe market domination of colossal conglomerates. Korean conglomerates, or chaebols, influence every aspect of Korean society. Samsung, for example, is not just a cell phone company. You can see Samsung logos from refrigerators to sportswear, and the services Samsung provides varies from insurance policies to hotel rooms. The share of the top 10 largest conglomerates’ assets among corporate groups have increased from 62.4% to 69.5% in 17 years. With their enormous market share, it is almost impossible for SMEs to fairly compete in the market. Even in the B2B market, chaebols tend to make contracts with their subsidiaries only. As a result, SMEs do not have a fair opportunity to compete with subsidiaries of these big conglomerates that already have a greater advantage in securing a deal. In March 2018, the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy hosted a conference to share the stories of SMEs that were mistreated by these chaebols including Hyundai, Hanhwa and Daewoo. SME owners claimed that these chaebols have stolen their technologies and required unfair contract or price cuts.

A large part of Korean technology innovation, product development, and foreign market penetration are from these giant corporations. Korean youths nowadays try as best as they can to get employed in chaebol companies instead of starting up their own business. The irony is that these chaebols are not creating many jobs in the market. The Council on Foreign Relations pointed out that chaebols are taking 77% of market profit, whereas creating only 10% of jobs in Korea. SMEs are the ones that employ almost 90% of workforce in Korean society. This shows that Korea needs to make a better ecosystem for startups and eliminate the barriers they face when they start to scale up.

There are several steps the Korean government should make in order to promote youth entrepreneurship. First, government should put less effort on hosting new business model competitions that do not impact youths to become entrepreneurs. An effective policy should focus on supporting technology-based startups that face financial burden in their third to seven-years of business. Furthermore, there should be strict screening process of entrepreneurship course recognition, and potentially add a practical aspect as a requirement. One last important factor is regulating conglomerates which have captured market power and engage in unfair practices. Korean youths are entering the public sector as job searching is getting harder and as unemployment worsens. Promoting youth entrepreneurship with the right education, and an environment that ensures fair competition, would provide youths with a more positive attitude in choosing to be entrepreneurs.

Lee Haein is a CIPE Asia Intern and a Asan Academy Fellow.

Published Date: June 27, 2019