Communities across Tunisia recently elected more than 7,200 new local leaders in the nation’s first municipal elections since 2011. Many of the politicians are promising to pursue reforms. They must also decide how to handle a backlog of laws already on the books, but not yet implemented. CIPE’s graduate intern in Tunisia, Emna Ben Romdhane, writes about a new measure that could change the lives of young entrepreneurs and shares why she hopes more reforms are on the way.

Since the 2011 revolution that ended a decades-long dictatorship, Tunisia’s economy has struggled, as prices, inflation, unemployment, and national debt continue to rise. The economy is the number-one priority for citizens and government, as sustained suffering fuels citizen discontentment with government, and thus with democracy.

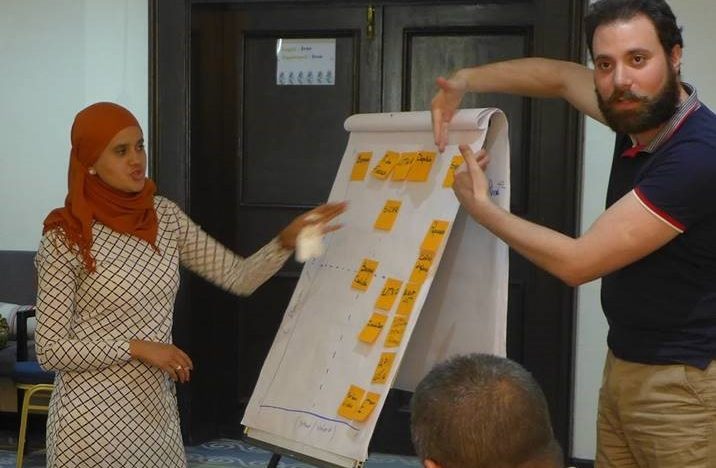

Young entrepreneurs participate in CIPE’s advocacy training in Tunis in May 2017. Here, they discuss which entrepreneurship stakeholders they should target.April 2, 2018 was a memorable day for the Tunisian entrepreneurship ecosystem. On that day, the Tunisian parliament adopted a new law that has the potential to change the private sector landscape and create opportunities for thousands of entrepreneurs around the country. The new law, called the Startup Act, aims to boost the Tunisian startup ecosystem by simplifying administrative procedures, facilitating access to finance, supporting startup creation, and opening access to international markets.

This law has been on the minds of entrepreneurs for over two years, which made its passage a bright moment for the startup ecosystem and for the Tunisian economy in general. The Startup Act aims to put sectors with high-growth potential, like science and technology, at the heart of the country’s economic transformation, instead of traditional sectors such as tourism and agriculture. It provides for increased access to finance for nascent businesses, reduces the number of bureaucratic procedures required to register and start a business, and promises to facilitate access to imports and exports. The Tunisian Startup Act can be considered a leading example on the African continent in terms of governments’ support for technology ecosystems. Among many other benefits, the law not only assists startups with funding and facilities, but also grants all employees, from both the private and public sectors, one year of leave from their current jobs in order to fully commit to their startups’ creation.

The law also suggests a framework to define which businesses qualify as startups, using the criteria below:

The law has the potential to create opportunity for thousands of entrepreneurs, specifically Tunisia’s innovation-minded young people. That said, what we should remember most about this law is how it was created and what brought it to the parliament. Tunisia’s parliament passed the Startup Act nearly unanimously with 100 votes in favor and just three abstentions. Such a landslide victory did not come without intensive stakeholder organization and advocacy efforts. Two years ago, a group of young entrepreneurs frustrated by the constant obstacles of navigating Tunisia’s bureaucracy took it upon themselves to propose reform of Tunisia’s startup culture. A few months in, civil society leaders, lawyers, capital investors, and several other stakeholders in the entrepreneurial ecosystem joined the movement. The process was supported by the involvement of every relevant stakeholder. One of the most important organizations that advocated the Startup Act was TunisianStartups, a business association representing the Tunisian startup sector whose mission is to create a legal environment conducive to entrepreneurship.

The law was first approved by the ministerial council on December 13, 2017. By that point, TunisianStartups had worked to secure widespread backing from the relevant government officials; their idea already had the support of the Ministry of Technology, Communication and Digital Economy; the Minister of Entrepreneurship; and the unconditional support of the Prime Minister. After securing this buy-in, a hearing was organized for members of parliament on March 5, 2018, and all entrepreneurial ecosystem actors were invited to attend. The hearing was followed by a meeting of the parliament’s Industrial Commission to debate the proposed law on March 8 and 9. The commission’s approval was the last step before the Startup Act was officially voted on and ultimately adopted by parliament.

The passage of this law is considered an achievement for the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and it brought a breath of fresh air to Tunisian youth, who were frustrated with the country’s lack of opportunity. On its face, the law’s passage seems like a victory with huge change-making potential. However, the Startup Act now joins a long line of laws awaiting “application regulations” — guidebooks for government ministries on how to implement laws — to ensure they are implemented evenly and transparently. Let’s hope it does not take two more years for this to happen!

Emna Ben Romdhane is a graduate intern at CIPE’s Tunisia field office.

Special thank you to Pamela Beecroft, CIPE’s Senior Program Officer for MENA, for the banner photography.

For more information:

Listen to a podcast about how the Tunisian business community has engaged with the government to advocate for economic reforms.

Read a blog post about a CIPE partnership in Guatemala that provided training to young entrepreneurs in creative fields.

Published Date: May 24, 2018